Podcast Available on iTunes and Spotify.

Welcome back.

Joining me today is Michelle Stanton, a Research Fellow in the Centre for Health, Informatics, Computing and Statistics at Lancaster University. She also holds an honorary position at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

She’s working on trying to reduce malaria deaths by better understanding where mosquito breeding spots are. To do this, she’s using the power of drones to capture aerial imagery in Malawi’s drone corridor – a patch of land devoted to humanitarian drone testing created by UNICEF.

Michelle, thanks for coming on the programme.

Thank you.

How are you using drones to fight malaria?

What we are currently doing, first trialling in Malawi, is see if we can use drones, particularly the camera attached to drones, to see if we can identify areas where mosquitoes are breeding. The reason why this is important is that malaria control programs can target breeding sites to stop the mosquitoes from being able to breed there. So we’re hoping that the information we can provide will help them more easily identify these areas to target and then hopefully reduce the prevalence of disease in the area.

And you worked alongside UNICEF for this work. What’s been the benefit of working with them?

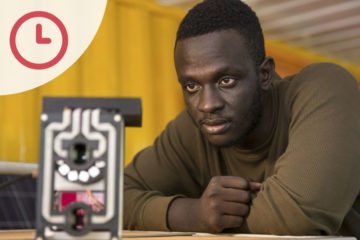

Many benefits. The primary one was that drones, as many people know, often have a bad reputation in the press as being things that are destructive rather than things that could be useful to society. So one of the problems that you have, when you try to organise a drone project, is to identify how you get permission to fly in an area. The work that I do which is primarily with tropical disease control, we didn’t really have those connections with places like the Civil Aviation Authority. UNICEF have seen this gap where drones could be used for good and have set up a testing corridor in Malawi and they invite people to come and trial their projects related to drones in that area. We were able to contact UNICEF, we’d already gained all the permissions that we would need to fly drones in Malawi, and bypass all the paperwork and go directly with them. They also have an internship program and so one of the interns at UNICEF, who was a local person called Patrick, was able to accompany us throughout the project and help with community engagement and sensitisation so that people knew why we were in the area flying the drones.

And presumably, when you’ve got a big loud drone going overhead, it’s going to draw in a bit of crowd. How much of your time was spent explaining what you were doing to the local residents and why you were doing it?

This is where the role of Patrick, the intern, really came into play. He was excellent in explaining exactly why we were there. As soon as we mentioned that it was related to malaria, generally the public were very positive and encouraging about us being there and there wasn’t any fear or suspicion about it, they were just genuinely interested in what we were doing and why we were doing it. It was really important not to come across negatively in the area as we are outsiders coming in flying something strange in the sky, we had to be really careful that we were seen positively.

What sort of results have you managed to obtain, what data were you collecting?

We were capturing images aerially with the camera pointing directly downwards. We were primarily focused on looking at reservoirs as during the dry season, these are areas where mosquitoes are most likely to be breeding. We were taking images of the reservoirs, particularly looking for vegetation around the edges of the reservoir as these are known areas for mosquito breeding sites. Then we have been processing those images to see if we can automatically identify the areas where we are most likely to find the mosquitoes. We’re still in the process of that now, it is the first trial of this particular technology that we’ve been involved in.

Who is funding this?

This was part of a project that I was funded for by the Medical Research Council. That funding has now come to an end so we’re looking now to see if we can extend this project by applying for future funding to repeat it in the dry and the wet seasons when temporary water bodies are going to be more important and perhaps more difficult to identify from the ground.

Michelle Stanton thank you.

Thank you.